Omega-3 fish oil is one of the most popular supplements for supporting heart, brain, and overall health. But not all fish oils are created equal. This comprehensive guide for health-conscious readers in Europe explores which fish provide the richest omega-3s (EPA, DHA, DPA), how fish oil is produced and handled from the fishing boat to the bottled supplement, why some fish carry heavy metals while others do not, which species boast the highest EPA, DHA, and DPA levels, and how to spot high-quality vs. low-quality (or even fake) fish oil supplements. All claims are backed by scientific research and industry data, with a focus on European practices and regulations.

Omega-3 Fatty Acids and the Best Fish Sources (EPA, DHA, DPA)

Omega-3 fatty acids come in several forms, but the most biologically important are the long-chain polyunsaturated fats EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid), DHA (docosahexaenoic acid), and the lesser-known DPA (docosapentaenoic acid). These are primarily obtained from marine foods. Cold-water oily fish are by far the richest sources of EPA and DHA, since these omega-3s originate in marine microalgae and concentrate up the food chain. In contrast, lean or warm-water fish contain much lower levels.

Top omega-3 fish: Cold-water fatty fish such as salmon, mackerel, herring, sardines, anchovies, and tuna are renowned for their high omega-3 content. For example, Atlantic mackerel and wild salmon can provide roughly 1.5–2.5 grams of EPA+DHA per 100 grams of fillet. In general, smaller oily fish like anchovy, sardine, and herring tend to have a higher percentage of their fat as omega-3 (often around 30% of total fatty acids in their oil). By contrast, fish with lower fat content – like cod, tilapia, or bass – contain only minimal omega-3 levels. Shellfish also have relatively low omega-3 compared to oily finfish.

EPA vs. DHA in fish: Different fish species vary in their EPA vs. DHA ratios. For instance, mackerel and sardines typically have a balance of EPA and DHA, whereas tuna and salmon are often especially high in DHA relative to EPA. These differences arise from diet and metabolism – algae at the base of the food chain produce both EPA and DHA, and fish accumulate them in varying proportions. DHA tends to be highest in fish like tuna, salmon, and trout, which is notable since DHA is crucial for brain and eye health. EPA, known for anti-inflammatory effects, is also abundant in these fish, often a few hundred milligrams per serving. Consumers looking to boost one or the other can choose their fish accordingly, though most oily fish provide a mix of both.

The “missing” omega-3 (DPA): DPA is an intermediate omega-3 between EPA and DHA that has recently attracted interest for its potential health benefits (e.g. anti-inflammatory and cardiovascular effects). DPA is much less commonly discussed because it’s relatively rare in foods. The principal sources of DPA are wild oceanic fish species, especially cold-water fish. However, even in these fish, DPA is present in smaller quantities compared to EPA and DHA. For example, in wild Atlantic salmon fillet, DPA might be a few percent of the total omega-3 content (exact amounts vary). Because fish don’t contain very high levels of DPA, the fish oil industry has historically focused on EPA and DHA. Still, some advanced supplements now advertise DPA content as well, recognizing its unique contributions to health. It’s worth noting that DPA is not yet available in large-scale commercial isolation (unlike EPA/DHA concentrates) because no single fish source provides it in bulk – most fish oils will have only a modest amount of DPA.

Summary – best fish for omega-3: To maximize omega-3 (EPA+DHA) intake, small oily fish are the best bet. A quick ranking of favorites includes:

-

Anchovies and Sardines – Tiny but mighty, these fish often top the charts for omega-3 density. They are commonly used in high-quality fish oil supplements for their ~30% omega-3 oil content.

-

Mackerel (Atlantic) – A fatty fish providing around 1.5–2.5 g of EPA+DHA per 100 g fillet, making it one of the richest sources.

-

Herring – Whether Atlantic or Pacific, herring is traditionally valued for its oil, with roughly 1.5–1.8 g EPA+DHA per 100 g.

-

Salmon (Wild) – Rich in DHA in particular; a typical wild Atlantic salmon portion (~100 g) provides ~1.8 g of EPA+DHA. Farmed salmon also contains omega-3s but levels can vary with feed.

-

Trout and Tuna – These provide slightly lower omega-3 (around 1.0–1.6 g per 100 g), but tuna’s oil is highly rich in DHA. Tuna is often used for tuna oil supplements, though large tuna also carry mercury (addressed later).

By choosing oily fish a few times per week or using a quality fish oil made from them, consumers can obtain meaningful doses of EPA and DHA. Next, we’ll see how these fish are transformed into the supplements on store shelves.

From boat to bottle: the omega-3 fish oil supply chain

Have you ever wondered how fish oil gets from the ocean to a capsule? The journey involves a complex supply chain from wild fisheries to refining facilities to encapsulation. In Europe, many leading omega-3 supplement brands source their oil globally (e.g. from the Atlantic or Pacific oceans) but process and bottle it under stringent quality controls. Understanding this “boat to bottle” process can illuminate why product quality and prices vary.

1. Catching the Fish – Species, Seasons, and Locations

Omega-3 fish oil production starts with harvesting oily fish. Globally and in Europe, the small pelagic fish (those low on the food chain) dominate fish oil production. These include anchovy, sardine, mackerel, menhaden, sprat, and similar species often termed “forage fish.” For instance, the Peruvian anchoveta (anchovy) fishery is the largest single source of fish oil worldwide, with annual catches ranging from 3 to 7 million tonnes that strongly influence global oil supply. In fact, variations in Peru’s anchovy catch (driven by natural cycles like El Niño) cause major swings in fish oil availability and price. Europe’s fish oil industry also relies on small pelagics like North Atlantic sprat, sand eel, capelin, and Norway pout, as well as by-products from food fish processing (e.g. cod livers, tuna offcuts).

When and where are fish caught? It depends on the species and regional regulations. Many small fish are caught in seasonal “campaigns.” For example, Peru typically has two main anchovy fishing seasons (dictated by quotas and ocean conditions) – one in summer and one in winter. If a season is cancelled or shortened (as happened in 2022–2023 due to too many juvenile fish), the oil supply tightens. In European waters, fisheries for species like capelin or sand eel also have specific seasons and quota limits to prevent overfishing. Much of Europe’s fish oil (about 20% of world production) comes from fisheries in the Northeast Atlantic (Norway, Iceland, Denmark). These fisheries are generally well-regulated for sustainability, with oversight by national agencies and adherence to EU hygiene regulations for fish oil production. Some European fish oil producers also import crude fish oil from elsewhere (like South America or West Africa) when local supply is insufficient.

Quality at the source: A critical factor is that fish used for oil are typically processed very soon after capture to preserve freshness. Many reduction fisheries (those turning fish into oil and meal) operate factory ships or coastal plants where the fish are cooked and pressed within hours of being caught. This helps minimize degradation. Nonetheless, if fish are left unrefrigerated too long, the oil can start oxidizing even before extraction, affecting quality. European producers often emphasize careful handling “from capture until it is bottled” to ensure freshness.

2. From whole fish to crude oil – processing and price factors

Once landed, the fish undergo a reduction process: they are cooked, pressed, and centrifuged to separate the oil from protein and water. The solid protein becomes fishmeal (used for animal feed), and the raw oil is collected as crude fish oil. This crude oil is the unrefined ingredient that will later be purified for supplements. The yield of oil can vary (small fatty fish may be 5-15% oil by weight). Factors like the fat content of fish (which peaks in certain seasons) will influence how much oil is obtained.

Pricing of crude fish oil: The price of crude fish oil fluctuates like any commodity, driven by supply and demand. Key factors include: fish catch volumes (a poor fishing season means less oil and higher prices), global demand (especially from aquaculture feed vs. supplement industries), and even related markets like vegetable oils. For instance, in recent years fish oil prices spiked when the Peruvian anchovy quota was cut – in 2022, crude fish oil production was markedly lower than previous years, causing prices to rise. Many refiners responded by using stockpiled oil reserves, but by 2023 a supply squeeze had developed. Geopolitical and climate events also play a role: the war in Ukraine drove up vegetable oil prices (sunflower oil), which indirectly pushed fish oil prices higher because fishmeal/oil producers calculate costs in relation to other oils. Likewise, El Niño warming events can reduce fish fat content and yields, straining supply. All these factors mean crude fish oil prices can be volatile – impacting the cost of your bottle of omega-3s.

Crude oil transport: After extraction, crude fish oil is typically stored in large tanks and shipped to refining facilities. It’s often transported in bulk via tanker ships or trucks (for shorter distances). A vivid example: Greenpeace documented tankers carrying fish oil from West Africa to Europe, underscoring that fish oil is traded globally. In that case, over half a million tons of fish caught in West African waters each year were processed into fishmeal and fish oil and exported, including shipments to the European Union. Transporting oil requires careful handling – the oil is usually kept cool (but not solidified) and inert gas (nitrogen) may be used to blanket it and prevent oxidation during the voyage.

3. Refining and blending – from crude to consumer-ready

Refining the oil: Crude fish oil is not what you want to swallow – it can contain impurities like free fatty acids, oxidation products, environmental contaminants (e.g. PCBs, dioxins), and has a strong fishy odor/taste. European supplement-grade fish oils therefore undergo extensive refining. This typically includes steps such as neutralization (to remove free fatty acids), bleaching (to remove pigments), winterization (to filter out saturated fats that cloud the oil), and deodorization (a form of steam distillation to remove odors and volatile compounds). For high-concentration omega-3 supplements, molecular distillation or enzymatic processing is used to create concentrated fish oil (often as ethyl esters or re-esterified triglycerides) with EPA/DHA levels of 50-90%. These processes also remove many contaminants. EU regulations impose strict limits on toxins like dioxins and PCBs in fish oils intended for human consumption, which refining helps achieve. Notably, heavy metals like mercury are largely removed by virtue of not concentrating in the oil phase (more on that later).

Blending of batches: One little-known industry practice is that manufacturers may blend fish oils from different batches or years to achieve consistency. Fish oil production can vary year to year in omega-3 content and volume. To deliver a standardized EPA/DHA content, companies often mix oils from multiple sources. For example, if one batch is a bit lower in EPA, it can be blended with another higher-EPA batch to meet the product specification on the label. Blending is also used to manage inventory – during poor catch years, older stockpiles might be blended with fresh oil. Because properly stored fish oil can remain stable for years under inert gas, producers maintain strategic reserves. One report noted that after a weak fishing year, some refiners “chose to rely on existing stocks” of oil, resulting in lower inventories later. When blending, manufacturers take great care to prevent oxidation: mixing is done at cool temperatures under nitrogen to avoid introducing oxygen. The goal is a homogeneous, stable oil blend that will be used for encapsulation or bottling.

Cutting costs – the dark side: While reputable companies follow good manufacturing practices, there have been cases of adulteration in the fish oil industry. Because pure fish oil is relatively expensive, unscrupulous suppliers have tried diluting it with cheaper oils (like soybean, corn, or palm oil) or falsely marketing low-grade oils as premium. In fact, analysts note that fish oils are prone to economically motivated mislabeling or adulteration with low-cost animal fats or plant oils. This practice can cut production costs but cheats consumers, providing less omega-3 than advertised. Fortunately, advanced tests can detect this. A 2024 study used NMR spectroscopy to profile commercial omega-3 supplements and found evidence of adulteration in some products – one “fish oil” sample contained no detectable DHA at all, strongly indicating it wasn’t real fish oil. Adulteration isn’t new; it’s been reported in marine oils for over a century. Today, reputable European brands safeguard against this by requiring supplier transparency and testing each batch for authenticity (fatty acid profile) and purity. Still, the risk underscores why consumers need to choose trusted brands (we’ll cover how to spot these later).

4. Encapsulation and bottling

The final steps of the supply chain happen at nutraceutical factories where oil is packaged for consumers. Most fish oil in Europe is sold as softgel capsules (gelatin capsules filled with oil) or as liquid in bottles. Softgels are popular because they neatly contain the oil and protect it from air. Manufacturers operate encapsulation lines that inject measured doses of oil into gelatin, then dry and seal the capsules. Throughout this process, oxidation must be rigorously controlled: oxygen exposure is minimized and antioxidants like mixed tocopherols (vitamin E) are often added to the oil to prolong shelf life. The finished capsules are flushed with nitrogen and packed in air-tight bottles or blister packs.

High-quality producers test the peroxide value (a measure of primary oxidation) of the final product to ensure it’s below recommended thresholds (typically PV < 5 meq/kg per industry standards).

For liquid fish oils (like bottled omega-3 oils often sold in Europe), bottling is done with special care to exclude air – amber glass bottles are filled under nitrogen and sealed. These liquids usually contain flavorings (e.g. lemon oil) to mask any fishy taste and further antioxidants (like rosemary extract) to stabilize the oil. Once sealed and packaged, the product is ready for distribution to stores and consumers. From the initial catch on a boat to the final bottle on a shelf, the oil may have traveled thousands of kilometers and undergone numerous quality checks. Next, we address a common consumer concern during this journey: heavy metal contamination.

Heavy metals in fish: why some fish (and fish oils) contain toxins and others don’t

Consumers are often warned about mercury and other heavy metals in seafood. It’s true that certain fish accumulate concerning levels of heavy metals – but others have negligible amounts. What explains this difference, and how does it affect fish oil supplements?

Bioaccumulation and fish size: The primary reason some fish contain high heavy metals (like mercury, arsenic, cadmium, lead) is their position in the food chain and lifespan. Large predatory fish that live a long time – think shark, swordfish, king mackerel, big tuna – build up mercury with each meal of smaller fish. Mercury (especially methylmercury) binds to proteins in fish tissue and isn’t easily excreted, so levels increase over years. Studies confirm that mercury content in fish increases with age, weight, and length of the fish. For example, a young small tuna will have much less mercury than an old large tuna. One analysis of fish in Poland found the highest mercury concentration in tuna, at 0.827 mg/kg, whereas smaller species had levels near 0.004–0.1 mg/kg. Generally, top predators and long-lived species have the most heavy metal buildup, while short-lived, small species (anchovy, sardine, herring) have extremely low levels in comparison.

Environment and diet: Another factor is where the fish lives and what it eats. Fish in polluted waters (e.g. industrialized bays) can take up more heavy metals from water and sediments. However, mercury in the ocean broadly comes from both natural sources and pollution, and it magnifies up the food chain. The small plankton and algae have tiny mercury levels, small fish accumulate a bit more, and big fish end up with the most. Interestingly, oily fish vs. lean fish doesn’t inherently matter for mercury – mercury isn’t higher in fat, it binds to muscle. In fact, the mercury content is not related to the fat content of the fish. So an “oily fish” like sardine isn’t high in mercury just because it’s oily – it stays low in mercury because it’s small and low on the food web. This is good news: the very fish we prize for omega-3 (like sardine and anchovy) are the ones with minimal heavy metal risk.

Fish oil purification: When it comes to fish oil supplements, heavy metals are much less of a concern than in whole fish consumption. Firstly, fish oil is derived predominantly from low-mercury species (for example, anchovy, menhaden, cod liver). Secondly, mercury is a water-soluble metal that tends to associate with protein tissue, not the oil. Measurements bear this out: one study found fish oils contained on average 0.088 µg/kg of mercury, which was even less than the trace found in some vegetable oils. This level is hundreds of times lower than mercury limits for fish meat, effectively negligible. Additionally, during oil refining, any heavy metals that might be present in the crude oil (e.g. from processing equipment or minor contamination) can be filtered out along with other impurities.

What about other contaminants? While mercury and lead are virtually absent in quality fish oils, organic pollutants like PCBs and dioxins – which are fat-soluble – can be a concern. These environmental toxins can accumulate in fish oil if the source fish lived in contaminated waters. European regulations have strict maximum levels for PCBs/dioxins in fish oils (since these can cause harm over time), so reputable producers test each batch and often source from cleaner waters. Modern distillation techniques can reduce these contaminants to well below regulatory limits. For example, oils from fish caught in pristine areas like the South Pacific or North Atlantic generally have very low pollutant levels, whereas fish from heavily industrialized regions might require extra purification. Top omega-3 brands often publish or provide purity data showing nondetectable heavy metals and compliance with EU contaminant limits.

Bottom line on heavy metals: The small, oily fish used for supplements are naturally low in heavy metals, and the manufacturing process further ensures the final oil is safe. That’s why you will rarely, if ever, see warnings about mercury on fish oil supplements (even though such warnings exist for certain fish you buy at the fishmonger). If one sticks to fish oils made from anchovy, sardine, herring, or purified cod liver oil, heavy metal exposure is minimal. Consumers should, however, avoid omega-3 products made from large predatory fish (like shark oil or unrefined tuna oil), as those could carry more contaminants – these are uncommon on the European market precisely due to that issue. The next section will list which species’ oils are highest in the desired omega-3s (EPA, DHA, DPA) – fortunately, they’re the same ones that are lowest in toxins.

Which fish species boast the highest EPA, DHA, and DPA?

We’ve touched on various fish, but here we’ll explicitly identify which species yield the most EPA, DHA, and DPA – useful whether you’re choosing a fish to eat or checking what’s in your supplement.

-

Anchovy (Engraulis ringens, etc.): A star of the omega-3 world, anchovies are tiny but rich in oil. Fish oil manufacturers favor Peruvian anchovy for supplements. Anchovy oil is typically about 30% EPA+DHA by weight. EPA and DHA levels are roughly equal in anchovy. DPA is present at low levels (a few percent of total omega-3). Because anchovies are so abundant and oily, anchovy oil is found in many European supplements (often labeled as “fish body oil” or “anchovy/sardine oil”).

-

Sardine (Sardinops spp. or Sardina pilchardus): Very similar to anchovy in omega-3 content. Sardines (including European pilchard) have around 1.0–1.4 g of EPA+DHA per 100g fillet. Sardine oil is rich in EPA and DHA (again ~30% of fatty acids). Sardines are a common supplement source, sometimes listed alongside anchovy. They also contain minor DPA.

-

Mackerel (Scomber scombrus – Atlantic mackerel): One of the fattier fish, with about 2.5 g of EPA+DHA per 100g. Mackerel’s oil is high in DHA. It’s less used in supplements (because mackerel is often eaten fresh, and its strong flavor can carry into oil). Nonetheless, some products, especially in Europe and Asia, do use mackerel oil. King mackerel (a larger species) also has omega-3 but is high in mercury, so it’s avoided for supplements.

-

Herring (Clupea harengus): Herring has long been used to make fish oil and liver oils. Atlantic herring provides ~1.6–1.7 g EPA+DHA per 100g. It’s rich in EPA relative to DHA. Herring oil and its close cousin menhaden oil (from a related fish in North America) are major sources for bulk omega-3 production (especially for animal feed, but also purified for humans). Herring also contains some DPA.

-

Salmon (Salmo salar – Atlantic salmon, and others): Salmon is prized for DHA. Wild Atlantic salmon has ~1.8 g EPA+DHA per 100g, and even farmed salmon around 1.5–2 g. Salmon oil supplements are popular in Europe; they are often marketed as “natural salmon oil” for those who prefer a single-species oil. Salmon oil typically has a higher DHA:EPA ratio (DHA often about twice EPA). It also naturally contains astaxanthin, an antioxidant (which gives salmon flesh its pink color). Salmon oil usually contains a small amount of DPA too. One caveat: much of the salmon on the market is farmed; oil extracted from farmed salmon may have a slightly different fatty profile (and lower omega-3 if the feed is not rich in omega-3). High-quality salmon oil supplements often come from wild Alaskan salmon for this reason.

-

Cod (Gadus morhua) – specifically cod liver oil: Cod itself is a lean fish, but its liver is rich in oil. Cod liver oil is a traditional omega-3 source in Europe, valued not only for EPA/DHA but also for vitamins A and D. Cod liver oil typically contains a bit less EPA+DHA (about 20% of the oil) and more monounsaturated fats, but it still provides a good dose and some DPA. Many European consumers take cod liver oil in winter for vitamin D – it’s a slightly different proposition than generic fish body oil.

-

Krill (Euphausia superba): Not a fish, but worth mentioning as a marine omega-3 source. Krill oil (from Antarctic krill) contains EPA and DHA mostly in phospholipid form. Its total EPA+DHA content is lower (around 20% of oil) but it contains astaxanthin and is reputed to be well-absorbed. Krill are tiny and low in contaminants. Krill oil is popular in some markets, including Europe, as a premium alternative – though typically more expensive per omega-3 amount.

EPA vs. DHA rich fish: If you specifically want more EPA (for inflammation or mood support, for example), consider oils from anchovy, sardine, herring, which have a good balance or slightly more EPA. For maximum DHA (for brain, pregnancy, etc.), tuna oil and algal oil are highest, but tuna oil can carry mercury if not well refined. Some supplements use tuna oil concentrates or calamari oil (from squid) which is very high in DHA. DPA tends to come along for the ride in many of these oils in small amounts – there’s currently no way to get a high-DPA fish oil except some specialized blends that concentrate what little DPA is available.

In summary, small, oily fish species are the winners for EPA and DHA content, and they are the ones most frequently listed as sources on European fish oil supplement labels (check for anchovy, sardine, mackerel, herring, or salmon on the ingredient list). Now that we’ve covered where the omega-3s come from, let’s turn to the practical matter of picking a good supplement off the store shelf and avoiding those that don’t live up to their promises.

A consumer’s guide to quality: how to spot high-quality (and avoid low-quality or fake) fish oil supplements

Standing in front of a shelf of fish oil supplements, how can you tell which one is worth your money and safe to consume? Unfortunately, not all products are equal. Studies have found issues ranging from lower omega-3 content than claimed, to oxidized (rancid) oils, to adulteration with cheaper oils. But there are clear indicators of quality you can look for on the label and packaging. Below is a science-based guide for consumers in Europe to analyze fish oil products:

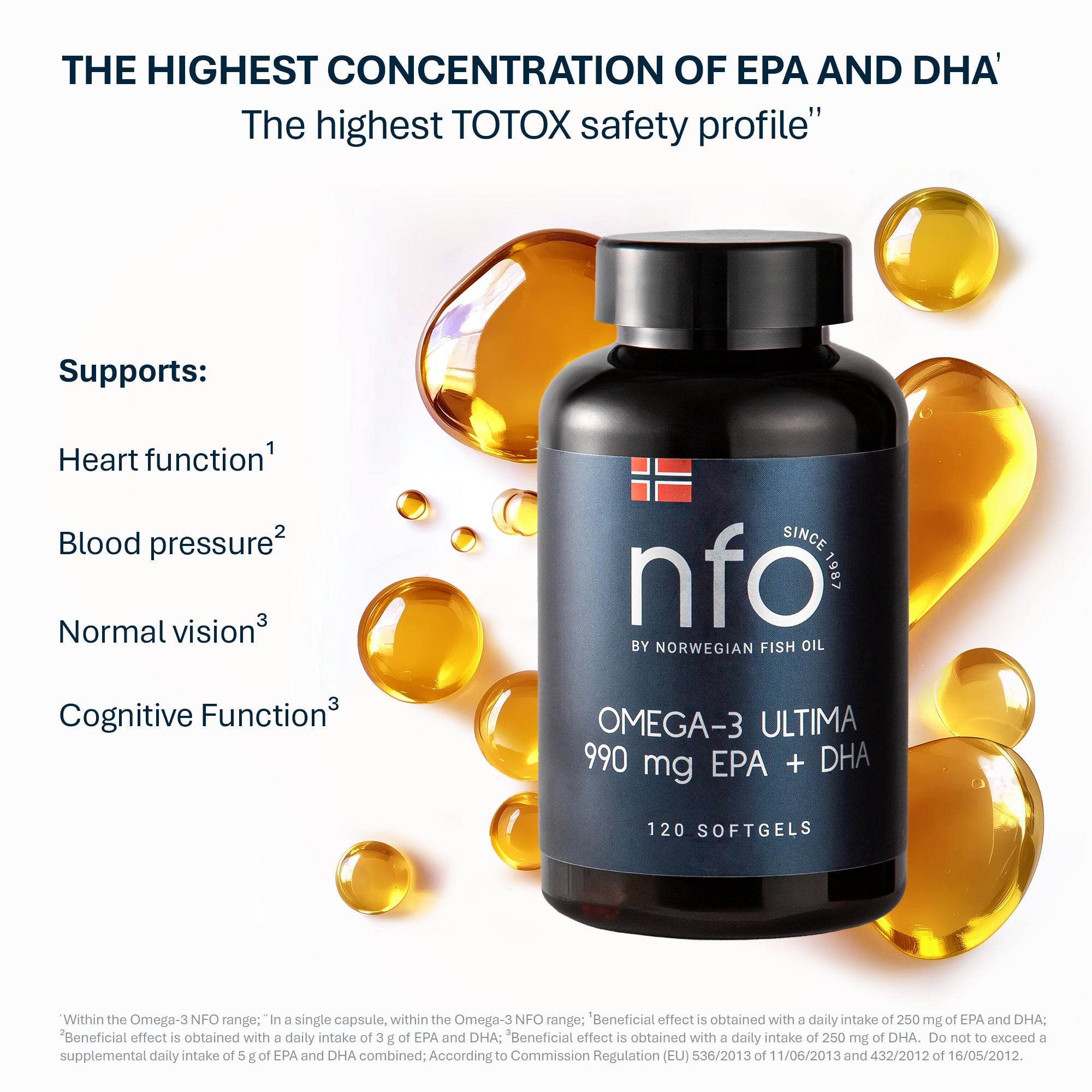

1. Read the EPA/DHA content on the label (not just “Fish Oil” amount)

The front of a bottle might boast “1000 mg Fish Oil” – but flip it to the nutrition panel for the real info. High-quality supplements will specify the amounts of EPA and DHA per serving (for example, EPA 400 mg, DHA 300 mg per 2 capsules). Lower-quality or “economy” products often have much lower concentrations – e.g. only 180 mg EPA and 120 mg DHA in a 1000 mg capsule, which is a very standard but low potency ratio. If a label doesn’t clearly list the EPA and DHA, or if those numbers are very small, that’s a red flag for a weak product. Consumers seeking therapeutic omega-3 doses might aim for products that provide at least ~500 mg combined EPA+DHA per capsule (50% concentration) or higher. Labels that only tell you the total fish oil amount but not the breakdown could be trying to mask a lot of filler oil with little omega-3.

Also, check the serving size: some brands deceptively list omega-3 content “per serving” where a serving might be 3-4 capsules.

Always calculate how much EPA/DHA you get per capsule or per 1 gram of oil to compare products accurately.

2. Check for purity and quality certifications or testing

Trustworthy companies often go the extra mile to verify quality. On the label or website, look for mentions of third-party testing or quality seals. Examples include IFOS (International Fish Oil Standards) 5-star certification, which tests for purity and oxidation, or GMP (Good Manufacturing Practice) certifications. Some European brands might show the EP or USP pharmacopoeia standards compliance. A label that says “tested for heavy metals and purity” indicates the manufacturer cares about these issues (though it’s even better if they provide actual results or a certificate of analysis).

3. Inspect the ingredient list for clarity and additives

A good fish oil supplement typically has a short ingredient list: something like “Fish oil (from anchovy, sardine), gelatin, glycerol, water, mixed tocopherols (antioxidant)”. Watch out for unusual ingredients:

-

Avoid unknown “blends”: If the source just says “marine lipids” or “fish oil blend” without specifying species, it might be a mix of whatever was cheapest at the time. Legitimate blends will still list the species (e.g. anchovy, mackerel, etc.).

-

Added oils: Be cautious if you see other oils like soybean or sunflower oil added (sometimes labels will note “contains soy” because of an added oil or soy-derived vitamin E). A tiny amount of soy-derived tocopherol (vitamin E) as an antioxidant is fine, but if soybean oil is a major ingredient, the product could be diluted.

-

Fillers and flavors: Flavored fish oils (like lemon flavor) are common especially in liquids or chewable capsules – that’s okay and often masks fishiness. But if you see a lot of unnecessary additives, question why.

Also, note if the form of omega-3 is mentioned (ethyl ester vs triglyceride form). Some high-end products pride themselves on “natural triglyceride” form fish oil. Ethyl esters are not inherently “fake” (many concentrated omega-3s are ethyl esters), but triglyceride form may be better absorbed. The key is that the label is transparent about what form and source you’re getting.

4. Look for freshness Indicators (expiry date, antioxidants, packaging)

Fish oil is prone to oxidation (rancidity) if not handled well. Rancid oil not only tastes and smells bad but may be less effective or even harmful. Here’s how to ensure you get a fresh product:

-

Expiration Date: Check that the “best by” or expiration date is reasonably far out (at least a year ahead, if not more). An expiring-soon product might have been on the shelf too long. However, note that “best-by date is a poor predictor of actual freshness” according to testing – some rancid products still fell within date. So use it as a basic check but not a guarantee.

-

Smell test (if possible): If you have access to open the bottle (after purchase), smell the capsules or liquid. It should have a neutral to mildly fishy smell, nothing strong, sour, or “rotten fish” like. Rancid oil often gives off a pungent aroma. Unfortunately, many capsule products are odorless until you bite into them. If you do experience “fishy burps” consistently with a product, that could indicate oxidation (or just that it’s not enteric coated). Be aware that manufacturers often add flavorings to mask fishy smell – peppermint, citrus, etc. can cover up rancidity. So an absence of fishy odor doesn’t always mean truly fresh (flavor could be hiding it).

-

Antioxidants: Check if the product includes antioxidants like mixed tocopherols, vitamin E, rosemary extract, or astaxanthin. These ingredients help protect the oil from oxidizing. Most quality oils will have at least vitamin E added. If a product has none listed, it might rely solely on processing for freshness, which can be fine if done well, but antioxidants are an extra safety net.

-

Packaging: Prefer dark-colored bottles (to avoid light exposure) and fully sealed caps. Some liquid fish oils are bottled with nitrogen gas padding – which is good. Individual blister-packed capsules can also stay fresher than a large jar that is opened repeatedly.

A striking stat: independent tests by the Pacific Labdoor and others have found that over 1 in 10 fish oil supplements on the market were rancid (oxidized) beyond acceptable limits, and nearly half were at the borderline of the maximum recommended oxidation level. Some products had oxidation levels 11 times higher than the limit – essentially rotten oil. Globally, it’s estimated about 20% of fish oil supplements exceed voluntary oxidation limits. This underscores the importance of choosing brands known for freshness. If a company publishes its peroxide value or Totox (total oxidation) values, that transparency is a good sign. As a consumer, you obviously can’t measure these at home, but the above tips help you gauge freshness indirectly.

5. Beware of too-good-to-be-true deals (adulteration and low doses)

If you see a huge bottle of fish oil for a very low price, be cautious. While there are economical options, extremely cheap products might be cutting corners. As mentioned earlier, adulteration can occur – blending fish oil with cheaper oils. This is hard to detect without lab equipment, but one clue could be the omega-3 potency. If an oil claims to be fish oil but has an oddly low EPA/DHA content (and not due to being cod liver oil with vitamins or krill), something might be fishy. For example, one analysis found a “fish oil” supplement that had zero DHA, which is biologically implausible unless it was mostly soybean oil. Reputable companies will ensure a minimum level of EPA and DHA is present and will list it.

Also watch for the word “proprietary blend” in the supplement facts – in omega-3 supplements, there’s usually no need for a proprietary blend of oils. That could hide the inclusion of undesired oils. Similarly, check the serving size vs. bottle count vs. price: if you need to take 4 capsules to get a decent dose, that “120 capsule” bottle is actually only 30 servings, which might not be as great a deal as it looks.

6. Additional tips specific to Europe:

European Union regulations treat fish oil supplements as foods, and there are rules on labeling. For example, additives and allergens (like soy) must be declared. Look for labels in your language and an EU address for the manufacturer or importer, which signals it complies with EU standards. Sometimes very cheap supplements online might be imports that don’t fully comply – avoid those.

EU laws don’t mandate oxidation or purity disclosures on labels, but trustworthy European brands often adhere to the GOED Voluntary Monograph limits (peroxide, anisidine, etc.). You can inquire on company websites or customer service for a certificate of analysis (CoA). Many will provide data showing the product passed tests for peroxide value, heavy metals, etc. If a company cannot furnish evidence of quality testing, think twice.

Finally, remember that liquid vs. capsule is a personal choice – liquids can deliver high doses easily and are often fresher (shorter supply chain from bulk oil to bottle), but some people hate the taste. Capsules are convenient and tasteless, but you may need to take a handful to get a large dose of omega-3. Quality can be high or low in either form; the above guidance applies to both.

Conclusion

Omega-3 fish oil remains a valuable supplement for many, but it pays to be informed about its journey and quality. The best omega-3 sources are small, oily fish packed with EPA and DHA (and a dash of DPA) – conveniently, these are also the fish lowest in heavy metals. The European fish oil industry sources these fish from sustainable fisheries around the world, renders crude oil on board or on shore, then refines and blends it into the high-purity oils we find in supplements. However, not all products on the shelf meet the highest standards. By understanding the supply chain and the common issues (rancidity, dilution, mislabeling), consumers can better judge which fish oil to trust. In summary, choose fish oils that clearly state their omega-3 content and fish source, come from reputable companies with quality testing, and are packaged to preserve freshness. Armed with the knowledge and tips from this guide, you can confidently navigate the “boat to bottle” journey of fish oil and select a supplement that delivers the omega-3 benefits you seek – without the fraud or the funk.

References

-

NIH Office of Dietary Supplements – Omega-3 Fatty Acids Fact Sheet (Accessed 2025).

-

VKM (Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety) Report (2011) – Production and Oxidation of Marine Oils.

-

EUMOFA – European Market Observatory Report (2019) – Fishmeal and Fish Oil Case Study.

-

GOED – Global Organization for EPA/DHA Omega-3 (2023) – Global Fish Oil Supply Update.

-

Greenpeace/Maritime Executive (2021) – Fish Oil Tanker Intercept in English Channel.

-

Hasanpour et al. (2024) J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. – NMR Analysis of Omega-3 Supplements.

-

Wietecha-Posłuszny & Malek (2022) Molecules – Detection of Adulterants in Marine Oils.

-

Kozlova et al. (2023) Foods – Mercury Content in Fish for Consumption (Poland).

-

EFSA CONTAM Panel (2012) – Statement on mercury in fish (EFSA Journal).

-

Albert et al. (2015) Sci. Rep. – Quality of Fish Oil Supplements in NZ.

-

Syal, R. – The Guardian (17 Jan 2022) – Omega-3 Supplements Rancidity Investigation.

-

AquaOmega (2023) – Rising Costs of Fish Oil Blog. (Industry perspective on price factors)